Originally published in Army AL&T Magazine

In the field of personal finance, understanding human behavior has long been recognized as critical to individuals achieving financial independence and security. Most financial planning experts agree that if you have the time, desire and knowledge (expertise and experience), then hiring a financial planning professional may not be necessary. However, even if you do have the time, desire and requisite knowledge, there still may be value in hiring a professional because of their independence and impartiality. In other words, the professional “protects us from ourselves.”

In personal finance, countless studies have shown that individuals tend to make financial decisions that are emotionally driven and not in their own best interests, rather than objectively driven and based on data and analysis. This study of how people make personal financial decisions is often referred to as behavioral finance, an area where financial planning professionals bring real, measurable value to their clients. They keep their clients from making financial decisions based on emotions or biases.

SO HOW IS THIS RELATED TO DEFENSE ACQUISITION?

Acquisition professionals provide this type of value to senior defense leaders for acquisition programs. Understanding and studying the human part of the acquisition sciences may be the single most critical aspect to achieving better success and effectiveness in defense acquisition. Senior acquisition leaders across DOD often proclaim that the defense acquisition system’s most important asset is its people—the professionals in the acquisition workforce. However, investments in the education and training of these professionals often take a backseat to other higher priorities during annual funding drills in the planning, programing and budgeting process. It is simply hard to justify an investment in education over funding an acquisition program that provides tangible products and services for warfighters—even though the return on investment in our people may be orders of magnitude better than the return on investment of an acquisition program of record, prototyping effort or experiment.

Acquisition professionals are the most important asset in the defense acquisition system. They protect the interests of the warfighter and increase combat effectiveness by leading acquisition efforts and making make wise decisions.

Acquisition professionals also “protect senior leaders from themselves” with independent, objective, fact-based, data-driven analysis and recommendations. To do this well, acquisition professionals need education and training in all the fields of acquisition sciences (program management, contracting, engineering, test and evaluation, life cycle logistics and financial management and cost estimating) along with a deep understanding of human behavior and organizational dynamics. Specifically, I have coined the phrase behavioral acquisition, which explores defense acquisition from a behavioral standpoint, including the impact of psychology, organizational behavior and politics. Behavioral acquisition studies the decisions madein DOD acquisition programs and helps better understand and predict how acquisition professionals and senior leaders think and make decisions about program strategy, managing resources and leading people. Behavioral acquisition is analogous to behavioral finance, which has successfully applied social science theories—especially from psychology—to improve the accuracy of predictions about personal financial decisions.

DECISION-MAKING IN DEFENSE ACQUISITION

Given the complexity of the U.S. defense acquisition portfolio, better understanding how acquisition professionals, specifically program managers (PMs), make decisions would prove valuable for improving defense acquisition outcomes.

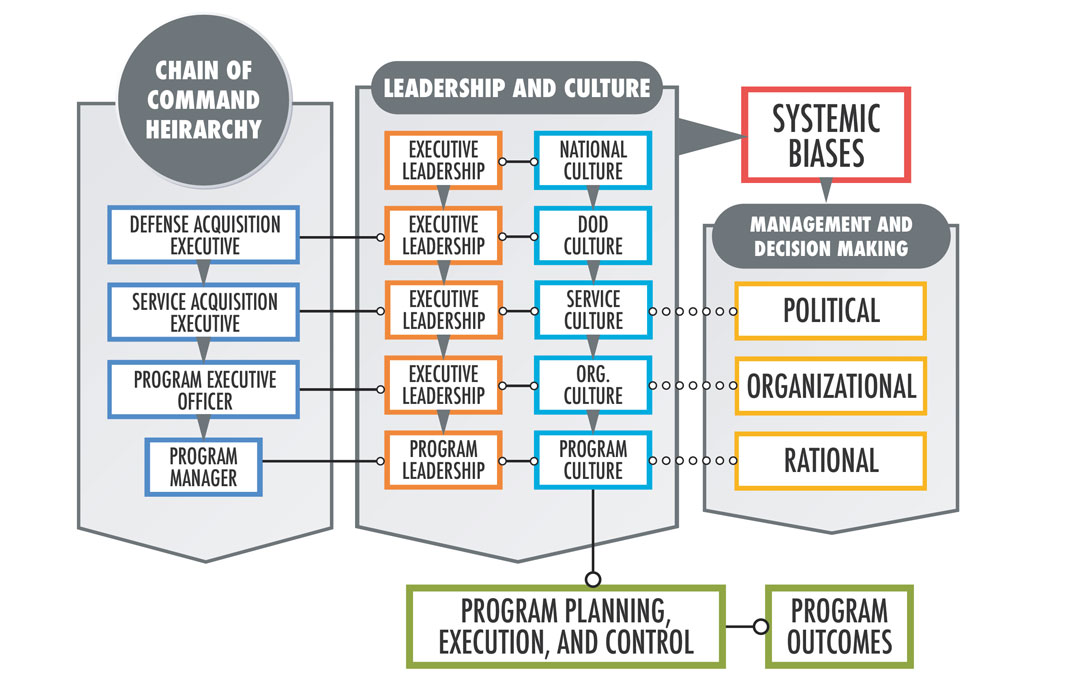

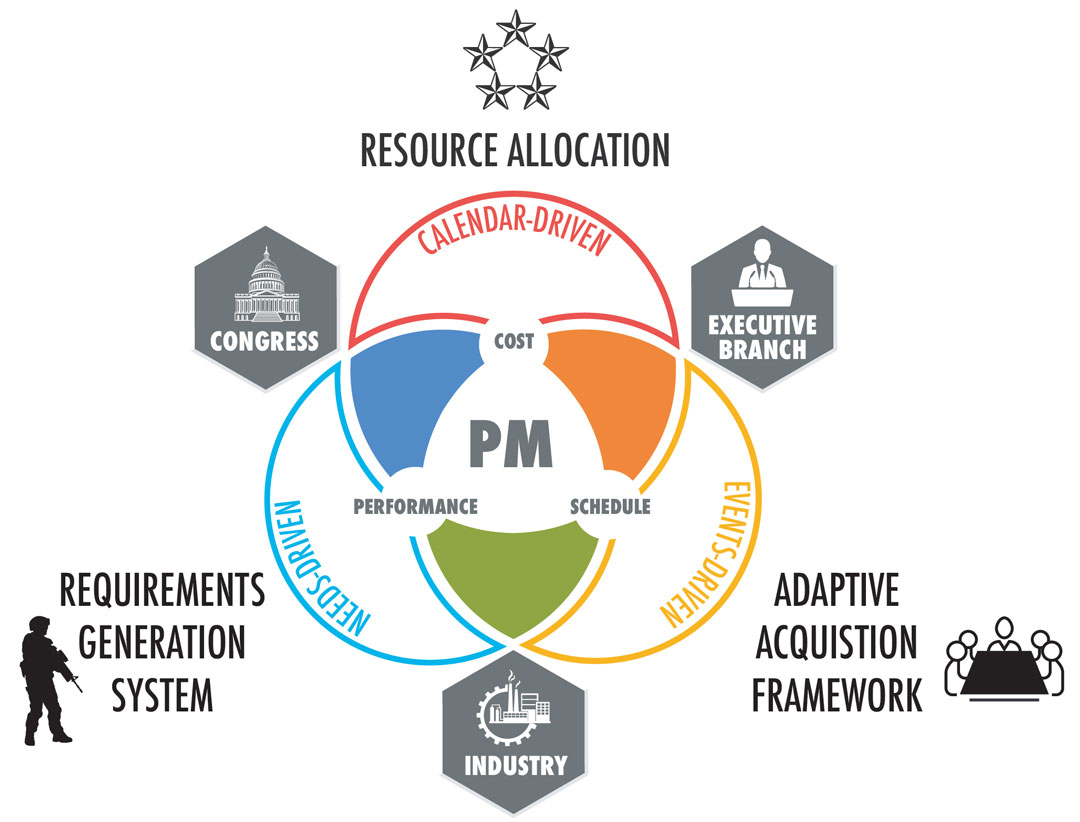

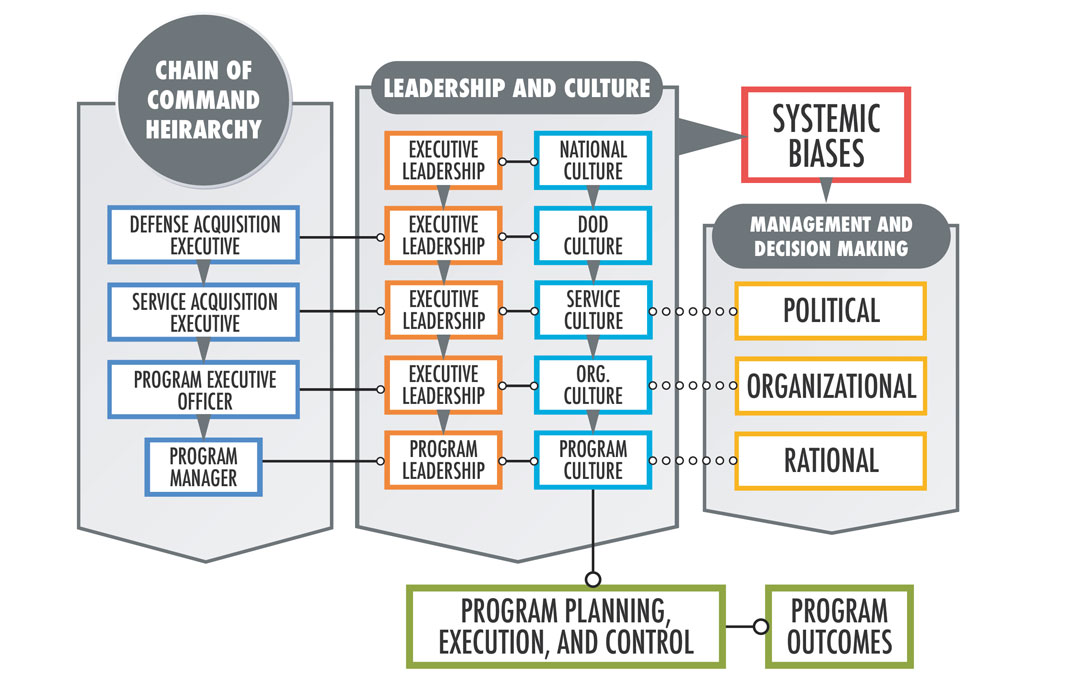

The PM is at the center of defense acquisition and is responsible the triple constraint of cost, schedule and performance for assigned projects. The PM has a hierarchal chain of command (or authority) through DOD in the executive branch. PMs report directly to a program executive officer, who reports to the Army, Navy or Air Force acquisition executive, who reports to the undersecretary of defense for acquisition and sustainment as the defense acquisition executive. Depending on the program’s visibility, importance and funding levels, a program’s milestone decision authority is assigned to the appropriate level of the chain of command.

As a backdrop to this complex acquisition environment for PMs, three decision support systems guide programs:

- The generation of requirements.

- The management of program milestones and knowledge points, known as the Adaptive Acquisition Framework (often referred to as “little ‘a’ acquisition”).

- The allocation of resources.

Each of these decision support systems is fundamentally driven by different and often contradictory factors. The requirement generation system is capability needs‑driven based on an evolving threat—requiring a responsive acquisition system. The resource allocation system is calendar-driven, with Congress writing an appropriations bill and the president signing the bill every fiscal year—providing control of funding to Congress and transparency to the public and media for taxpayer money. The Adaptive Acquisition Framework is event-driven by milestones—based on commercial industry best practices of knowledge points and off-ramps supported by the design, development and testing of the systems as technology matures and integration and manufacturing challenges occur. The combination of the PM triple constraint, chain of authority, acquisition environment and decision-support templates provides a framework to view U.S. defense acquisition, referred to as the defense acquisition institution (or “big ‘A’ acquisition”), depicted here.

Because of the inherent challenges involved with the development, procurement and fielding of sophisticated weapons systems that are required to operate reliably in challenging military environments, acquisition programs sometimes fail to deliver required performance capabilities within cost and schedule constraints. Root causes of acquisition program failures (schedule slips, cost overruns or capability underachievement) can be generally grouped into the following: ill-defined requirements, immature technology, integration challenges, poor cost estimating, unstable budgets, poor schedule planning and schedule pressure from annual appropriation limitations. But an underappreciated reason for acquisition program failures and an understudied part of big “A” acquisition is the “people part,” which may have the largest effect on improving acquisition outcomes. Behavioral acquisition includes a study of organizations and hierarchies and the intersection of individual behavior, leadership, culture and decision-making.

Decisions at the institutional (DOD) level are often made using a political conceptual model where decisions are a result of bargaining games and politics. And decisions at the organizational (service or PEO) level are often based on the appropriateness of the actions fitting the organization’s cultural norms. Whereas at the individual (program) level, decisions mostly leverage a rational conceptual model where decisions are based on logic and reasoning by assigning pros and cons and deciding the best chance of success. Important differences exist in how biases can affect leader decision-making in programs, organizations and institutions within DOD. The figure below presents an overall model showing the connection of hierarchical, leadership, cultural and behavior factors on management, decision-making and program outcomes.

BEHAVIORAL BIASES

Central to understanding decision processes in the defense acquisition environment is recognizing the impact that biases have on decision-making. These biases can be categorized into cognitive and emotional biases, but their common root is the ways in which human brains process information. There is a lack of research studying the effects of behavioral biases on decision-making in the defense acquisition environment. In general, acquisition programs are wide open to biases creeping into the program decision-making processes. Empirical case studies illustrate that acquisition programs are environments where there is abundant opportunity for behavioral biases to play a significant role in decision-making.

The following is a list of common behavioral biases often observed within defense acquisition programs that have affected decision-making and therefore program outcomes:

- Planning fallacy—“This time it’s different.”

- Difficulty making tradeoffs—“Everything is important, therefore nothing is.”

- Over-optimism—“Yes, we can do it,” or seeing things through “rose-colored glasses.”

- Recency bias—“Little chance of success unless this new initiative is incorporated.”

- Narrow or myopic framing of issues.

- Loss aversion when ahead and risk favoring when behind.

- Status quo bias or anchoring effect.

- Confirmation bias.

- Attribution bias—“Externalize failures or internalize successes.”

- Illusion of control.

- Availability heuristic—“In my last program …,” “Other programs right now … .”

- Narrative fallacy preference for stories over data.

- Framing effects—We are influenced by the way information is presented.

- Regret aversion.

- House money effects—Make us more risk-seeking.

- Hindsight bias.

- Blind spot bias—We think we are less prone to cognitive bias than those around us.

Recent acquisition reform directives and statutes require data-driven analysis and decisions, which put an emphasis on rational optimization. But whatever analysis tools are the fad or fashion of the day, decision-making inevitably still consists of people operating inside a program or organization trying to make decisions that deliver required outcomes. Hence, despite calls for more rationality, the organizational and political dimensions of decision-making matter, and these dimensions interact with behavioral biases in particular ways.

Research centering on the acknowledgment and study of bounded rationality has long recognized that people process information in ways that may lead them to make biased judgments. Cognitive biases are a two-edged sword: On the one hand they have a positive function in helping people to make fast decisions using limited cognitive resources. On the other, cognitive biases also lead people to make errors in decision-making that deviate—often in important ways—from rational decision-making.

Nonetheless, a basic premise of research into biases is that, as the volume and complexity of information increases, we are forced into using simplifying tactics that ration the limited cognitive resources we have available. Hence, we adopt heuristics that ease the cognitive strain. And because these heuristics involve rationing how information is processed, we develop systematic patterns of bias in decision-making.

CONCLUSION

That we see the effects of behavioral biases within the management and decision-making of acquisition programs comes as no surprise. For the past three decades, acquisition management has been highlighted on the Government Accountability Office’s high-risk list for excessive waste and mismanagement. Notable programs have failed to deliver capability and have failed to meet performance, cost and schedule management targets. The root causes of program failure vary from ill-defined requirements, immature technologies, integration challenges and poor cost estimating, to the acceptance of too much development risk. Underappreciated and understudied is the effect that systemic biases have on acquisition professionals and, more importantly, on acquisition program milestone decision authority, which contributes to the root causes of acquisition program failures. The better we understand the effect of these systemic behavioral biases, the better we can mitigate the risks of program failures resulting from poor or suboptimal decision-making.

The culture and leadership at different levels of DOD, from the institutional level to the organizational level to the program level, affect the impact of the biases. In DOD’s hierarchical chain of command, the PMs are responsible for the program’s cost, schedule and performance. However, the PMs do not establish the performance requirements, cost or schedule objectives of the acquisition program baseline—the services do. Additionally, PMs report to a milestone decision authority, who approves the program and determines overall program strategic direction. The systemic biases at the various levels of the chain of command manifest differently in the decision-making models used at different levels. Behavioral acquisition studies how culture, leadership, hierarchies and decision-making models moderate the effect of systemic behavioral biases with the goal of improving the management and execution of programs—ultimately improving program outcomes and satisfying warfighter requirements for better capabilities.